Health experts are warning that the United States is inching dangerously close to losing its measles elimination status, a milestone the country has held for a quarter of a century. Persistent outbreaks in Arizona and Utah have raised alarms within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and among global public health officials.

The CDC reports that a large-scale outbreak in Maricopa County, Arizona, has continued for nearly twelve consecutive months – a threshold that could cost the nation its measles-free designation. At least 85 infections have been confirmed in the county, making it one of the longest-running outbreaks the U.S. has seen in decades. Utah is also managing its own surge, with more than 1700 confirmed cases so far this year. In both states, the majority of infections have occurred among people who were not vaccinated.

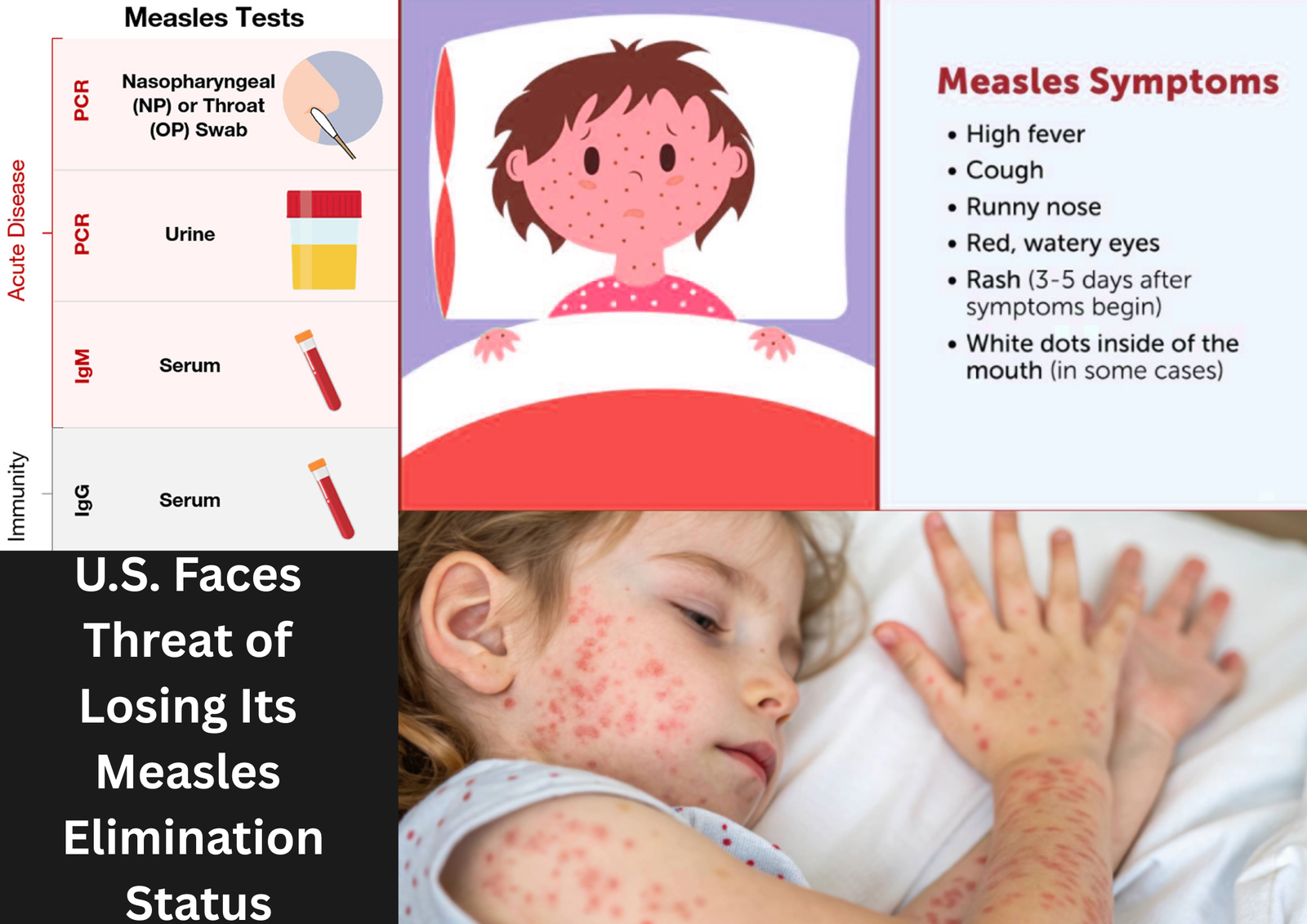

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known, capable of infecting up to 92 percent of unvaccinated individuals exposed to an infected person. The MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps, and rubella, remains highly effective. Two doses offer roughly 97 percent protection against the virus, yet many communities continue to show declining vaccine uptake.

If the U.S. loses its elimination status, it would mean that measles transmission has continued uninterrupted for more than a year – a clear sign that imported cases are no longer being contained. Several countries, including the United Kingdom, Greece, and Venezuela, have experienced similar setbacks in recent years after facing widespread outbreaks fueled by falling vaccination rates.

Head of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, called the situation “a serious warning signal.” He emphasized that strengthening vaccination coverage is the only way to prevent measles from regaining a foothold in the country. Federal teams are currently supporting state health agencies with testing, contact tracing, and public outreach to halt further transmission.

Measles is far from a harmless childhood illness. Complications can include pneumonia, severe dehydration, and encephalitis – a dangerous swelling of the brain. Children under five and adults over twenty face the highest risk. Before widespread vaccination began in the 1960s, the U.S. saw hundreds of deaths each year from the virus, along with thousands of hospitalizations.

Public health officials say the solution is straightforward: higher vaccination rates. They urge families and communities to ensure their immunizations are up to date, noting that widespread protection remains the only barrier preventing measles from becoming endemic in the U.S. once again.